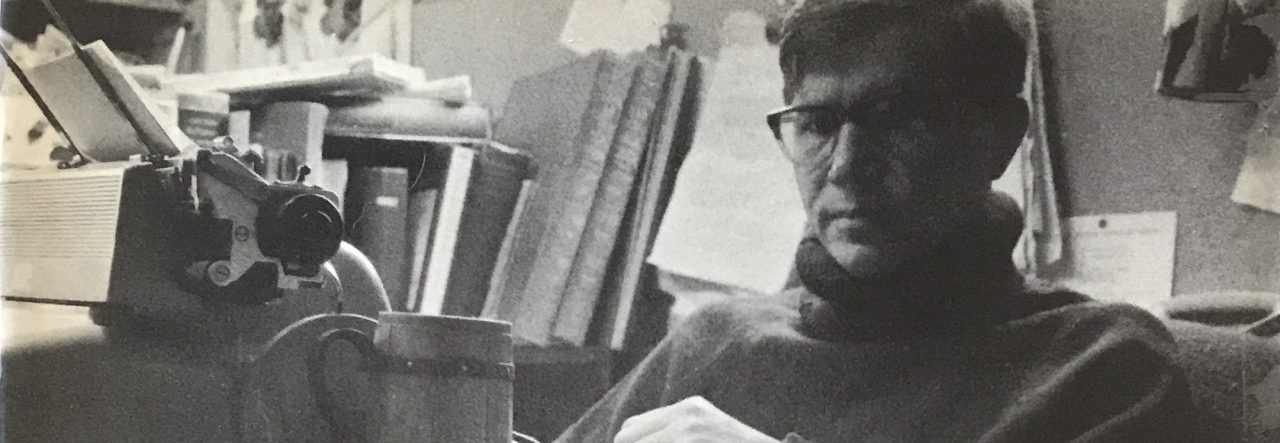

A longer version of On Death by CW scholar Vaughan Rapatahana. His compendium of CW critique, Philosophical (a)Musings is available now. A portion of his PhD thesis – Wilson as Mystic – is still available from Paupers’ Press.

On Death

Introduction:

It is time to take far more seriously our universal lack of emphasis on the event of death, which would seem – of course – a direct reversal of asking why life occurs in the first place, but which is not a corollary at all, for life is a given. Being is undeniable. So when, for example, Albert Camus cried:

There is but one truly serious philosophical problem and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy.

He was well wrong. We are already extant and will die anyway, regardless of his ‘freedom of choice.’ Suicide is merely an early enrollment in the final graduation programme.

I am inclined rather to concur with a writer like Ray Brassier, who tells us that in fact that it is precisely because there is death and ultimate extinction, that there is any life at all, thus any philosophy at all: “that it is only because life is conditioned by its own extinction that there is thought at all” as he scribes in his seminal tome Nihil Unbound: Enlightenment and Extinction (2007.) Philosophy is more truly a partner to non-Being. The truly serious and prime philosophical problem transmutes, then, to dealing with Death. Yet, of course, this subject of death has never been a ‘hot’ topic for most philosophers. It seems that there is a general lack of desire to even consider this universalized inevitability.

So, why do we all eventually, some far too soon, depart the scene? Why is there the deterioration of age and the often sad slink into Nothingness as opposed to Being, given that biologists will explain this as the inevitable degeneration of cells, and evolutionists will proclaim the need for death so as to encourage the next batches of life and as to maintain some living space for such?

My question is, however, a meta-question, seeking to override microcosmic physiological descriptions of this bodily degeneration and asking ‘Why is there Death, with a capital D?’ Why do we not look at others and see that in every living moment and with absolute clarity that one day they will no longer Be, and then not recoil in shock, in dread? Why are we also so damnably reluctant to self-acknowledge that our own death is inevitable? On a related or personal level, to even talk about it – our own death – down at the local? To even draw up specific death plans for our beloved to refer to when we do drop? We are necessarily contingent in hyperchaos, to paraphrase Quentin Meillassoux, but don’t ever seem to existentially internalize this.

Indeed thinkers as diverse as George Gurdjieff and Martin Heidegger expressly point out, over and over again, this inauthentic non-facing by up ‘Mankind’ to the sheer fact of Death at any given micro-second. Heidegger proclaims that ‘being-towards-death’ alone, as based on a profound experience of free-floating dread, can impel mankind towards some profound sense of their inevitable and impending and potentially immediate death at any given moment and thus enable them to grasp the sheer significance their life far more tightly. For Heidegger, once an individual is fully internally cognizant of their ability to die, they can commence to authentically exist. “As soon as man comes to life, he is at once old enough to die” (Heidegger, Being and Time,1962.) More, states, Heidegger, as expressly described by Diane Zorn (Heidegger’s Philosophy of Death, Akademia, 1991): “I alone will die my death. Since only I can know what it means for me to be going to die, death cannot be shared by anyone.”

Zorn summarizes here: “[Heidegger] interprets death as a meaningful possibility by showing that death is an existential awareness of possible not-being (ibid.)” – which, for me, at least, ties into what Brassier is himself stating: that non-being is the Ultimate Truth, given that Brassier himself would palpably see Heidegger as part of the Continental ‘correlationist’ tradition he – and other Speculative Realists – firmly disavow. Indeed Brassier sees Death as a totally non-human presence, an inevitability, or as Jon Lindblom (online, 2012) puts it so succinctly: “This is not a death that makes sense in our world – that is, the death of the individual that shapes our horizon and molds our project (Heidegger) – but an impersonal death, which, in a way, means that the philosopher is already dead, since philosophy is nothing but the anticipation (or ‘organon’, as Brassier puts it) of our own extinction, and the fact that we are already extinct, since we are not what we thought we were. Not rational agents operating in a meaningful world, but physical systems interacting in a flat, spatialized exteriority.” Brassier subtracts an individual ‘s eminent epistemological existence from the equation.

The Avoidance:

As opposed to this is the far more prevalent ‘they-self’ syndrome, whereby the crowd of mass-man/woman so influences an individual as to avoid facing up to Death, to in fact deplete it as a subject to not even think about, a “constant tranquilization about death… an untroubled indifference” (Heidegger, 1962.) Zorn once more: “The they-self tempts us to convince ourselves that death is not really our own, tranquillizes us against death-awareness because it cannot be shared by others, and thus alienates us from our authentic self by concealing death.”

Heidegger was here not alone in his notification about man’s forgetfulness of death, for: “Gurdjieff also said that people live as if they were going to live forever. In the back of their minds, they have the assumption that they’re immortal, even though they know intellectually that it’s not true” (Kevin Langdon, online, 1986) But – similarly to Heidegger, again – he also noted that: “one has moments of feeling one’s mortality, it begins to create that sense of urgency which is needed in order to remember to make efforts…He placed great emphasis on awareness of the inevitability of one’s own death. And he also suggested that it is useful to remember the mortality of everyone on whom, as he put it, “your eyes or attention rests” (ibid.)

Without doubt, the ‘they-self’ certainly reigns supreme. People die. At times their passing (to what? to where?) is recorded or mourned – and indeed, in the cases of ‘celebrities’ lengthy, often obsequious, obituaries are penned – but there is no serious questioning as to ‘Why is this person dead?’ The living all too often seize upon the occasion of death more to festoon themselves in pity, to self-gratify, as opposed to fully cognize the finality involved and declare an honest empathy for another’s departure once and for all. Sometimes a media medium also leaps onto a bizarre way of dying as a news item worthy of soliciting a wider gratuitous readership. More, certain other agencies actually profit from the proliferation of death: funeral directors, firearm sellers aka ‘merchants of death’, some bloodthirsty egotistical generals and politicians. They don’t want death to die out at all. But few, if any, take Death on board on their all too contingent voyage through life.

Worse still, if mass death occurs – particularly if it took place in non-Western countries – it is soon forgotten and quickly papered over by Western media sources, if it is even covered at all in the first place. Yet the departure of some long-forgotten Hollywood ‘star’ still rates a mention in TIME magazine. Over 1000 Filipinos wiped out in one day in Mindanao in early 2013 scarcely rates a mention in its white pages.

Death has become as undervalued as Life and is all so easily accomplished via – for example – a reckless handgun or for a helmet-less motorbike rider; through a mass-stoning or an immolation; in the midst of a suicide bombing (itself an aberration whereby one death leads to many deaths, supposedly to avenge still more deaths) or a state-sponsored execution, whereby another death somehow atones for earlier instances of same. All somewhat nutty behaviour, for the avoidance of the existential fact of death soothes the way for an incremental number of deaths..

We have become as desensitized to Death – witness the number of ‘kills’ racked up in any typical video game extravaganza – as we have to the preciousness of Life. Death is merely ‘accepted’ in passing and we quite literally quickly pass on to the next topic.

All rather odd. We should be fighting this death business as it is a manifest cop-out to be living for a certain amount of time, to accomplish a range of sometimes splendid activities, to love, to hate, to emote, to form strong bonds with loved ones and friends, and then to depart for good. This is the ‘true’ absurd, really. We should be placing far more serious attention on living, living longer, living better, fighting this death machinery. We are returning a gift to the store before it is fully appreciated. Here is where Colin Wilson, for example, clearly pointed out how ‘traditional’ Existentialism – a la Camus as one example – ‘failed’: it assumed suicide was somehow a freedom from death. In reality, suicide is merely impelling the inevitable.

Colin Wilson strides forward:

Now several thinkers have attempted to adumbrate prescriptions as to gaining more life, going further into life. Colin Wilson, again, comes to mind as a prime example – with his Introduction to the New Existentialism (1966) as just one earlier manifestation of his credo, where he also attempts to transcend Martin Heidegger’s own rather stoical appraisal of Death. However, Wilson only goes so far and ignores completely bodily death, indeed bodily presence per se. Indeed his whole thrust is purely a ‘mental’ one (I had pointed out in my own work, for example Wilson as Mystic, 2001 and more comprehensively in my earlier 1996 thesis, that Wilson writes as someone who tends to diminish, even detest body functions, as shown in his early novels in particular.) More, he also of course almost totally ignores bodily death (and disease and destruction in a wider social realm) to the absurd degree – especially early in his career – that he frequently proclaimed his own self-belief that he would sentiently live, if not forever, at least to age so as to run well over any human ‘norm’. Brassier – again, however – would claim that humanity has many self-important ‘conceits’ such as this, that require dismantling.

Sadly, Wilson never had a completely holistic approach to flogging death into submission, although all credit to him for stressing the impellment to far more life, to plunge more fully into the life-stream. However sheer mental strength or willpower is not simply going to defeat death, thus boost longevity. Wilson proclaimed in a 2003 interview with Geoff Ward (online): “Our purpose in the world is eventually to enable spirit to conquer matter, to get into matter to such an extent that there is no longer any matter.” This would seem an oversimplified underestimation of what is real, out there, extant beyond Mankind and what Wilson describes as “pure mind, intellect” (ibid.) Again, recent and younger thinkers such as Graham Harman and others of the Collapse ilk would categorically state that, as Ray Brassier noted in Nihil Unbound: “It is no longer thought that determines the object, whether through representation or intuition, but rather the object that seizes thought and forces it to think it, or better according to it.” Everything is in epistemological reversal.

Other striations:

Moving along, yes, there are also some historical approaches to this death business. A plenitude of ‘traditional’ religions such as Christianity and Islam have endeavoured – not particularly convincingly for this writer – to generate myths about Heaven (and Hell for that matter) and souls as a sop to the living, as a quasi-rationale for being here in the first place. But they don’t actually convince anyone with a modicum of sense that there is a need for death in the first place. They all too often grate as fairy tales told by school kids. These tales do not rate as serious rationalizations as to why we should die and indeed give the lie to what actually does eventuate when we die – we rot away. Simple as that.

Jesus Christ and Prophet Mohammad are long gone, R.I.P. They are not coming back. They are dead. Ironically, however, some of the living are also making great capital from them – priests, pontiffs and prelates. As well as imams and insurrectionists.

Then there are the parapsychological parrots who prate the ‘existence’ of near-death and return-from-death and reincarnation experiences as ‘evidence’ that in fact bodily death is not the be all and end all of existence. Leaving aside the huge miasmatic glob concerning bodies as opposed to something non-physical and nominated as ‘minds’ – itself a contentious and increasingly unlikely divide – there remains still no defining and cogent evidence that such ‘death’ experiences prove anything whatsoever and that – in fact – the sheer amorphousness of such ‘experiences’ serves to completely cloud the issue as to their veracity. There hasn’t ever been a 50% – let alone a 100% verifiable case –of a returned ‘departee’ and/or an extant ‘eternalee’, given – once again – the emphatic words of Colin Wilson in his account of afterlife. More, when Wilson says “But I do feel, nevertheless, that life after death is basically true, that we don’t actually die…it seems to me it’s just a basic fact” (ibid.) he could well be accused of making an almost Camus-type statement, which would certainly be the last thing on his mind. For if we don’t die and yet somehow transcend physiological existence (something Wilson, in all his earnestness, has yet to convince us of), why on Earth bother to hang around on Earth at all?

It is a major – no, I would go further and state that it is the prime concern that we all should face far more front-on – that in 2013 we still have no final consensus as to any proven post-biological-death existence in any field whatsoever. Quite the opposite, in fact, as science and neurophysiology in particular narrow the gaps in our knowledge, toward a completely physiological construction of the human frame. Both body and mind dwindle into one. Do you know anyone who has actually been resurrected, other than via electric shock therapy or strenuous heart massage? Do you know the Easter Bunny or Santa Claus? Enough said.

Except that I would also like to – somewhat ironically – further say here that it doesn’t actually matter if there is some sort of rather unlikely “another level of existence” (Wilson, ibid.) for bodily death does not necessarily negate a ‘life after death. However my consistent point throughout this essay is that this wayward possibility is not important for us as Being here now, and most definitely always facing our impending demises at any given nano-second, while no one essentially wants to actually dive into a Wilson-type afterlife either. Think also about the thoughts of another Speculative Realist, Martin Haggland: “Immortality is impossible…also it is not desirable in the first place” (Radical Atheist Materialism: A Critique of Meillassoux The Speculative Turn, 2011.) See also my points in the Postscript below.

A Sort of Summary:

All of which leads us back to the beginning of this essay: why is there Death as opposed to Life and why aren’t we far more mystified, concerned, in alarm, confused, aware than we most evidently are? We all require an immediate epiphany as to our impending demise at any given moment, whereby questions of ‘personal identity’ as to who/what actually dies are superseded immediately as irrelevant. Why aren’t we in awe that we all will die, that some of us will die in an alarmingly surprising and unpredictable way, and more wondrously, that we waste so much of our time actually encouraging our respective and unnecessary demise through idiotic dietary habits and smoking; through stupendously stupid testosterone-fuelled warfare and the curiously American penchant for building up more and more grotesquely, more and more new-fangled weapons of mass destruction; through to a belligerent turning a blind eye to the millions starving to death and dying of curable diseases; and to the thousands being blown up by the landmines left behind after another failed ‘liberating mission’? We – or at least many of us – also steadfastly destroy our environment so as to hasten our own contingent obliteration. We seem to encourage our own demise! We go out of our ways to actually increase the chances of death, yet are inevitably very wary of our own individual extinguishing. Obliteration will happen to us all anyway – so why are we so Hell bent on hastening it?

For no one – with the exception of the clinically depressed or the heavily euthanasiac – wishes to die. When that final curtain is being drawn down, we do our utmost to keep it open, given our bodies have not become too enfeebled to even resist.

So, why don’t we have far more departments of Death Studies in all of our educational institutions right now? International forums and colloquiums? Commissions of enquiry? Prizes for coming up with some actual answers to what should always be the main question: why do we (need to) die – although, admittedly, there are now some such awards for extending life spans? Why is Death such a prime overlooked component of our Lives, given what Heidegger noted about the ‘they-self’? Why do we basically ignore it, yet are happy enough to watch the F.A. Cup final in its incessant shadow? Death is not retreating, it’s not going away. It’s just outside our windows. It’s on the soccer pitch. It lurks in the grandstands and in the pubs outside after the match.

What are we doing here is not asking a question pertaining to why we are alive. Rather it is this query: why do we die and why aren’t we staring this BIG question in the face?

Do not accept another death without at the very least questioning it, fighting it, killing it. By confronting this dragon we may well slay it once and for all.

Life is a given. Death can be otherwise. Don’t let Death kill you.

On saying this – there are some who, even as I write, are practicing what I am preaching. See below:

Important Postscript:

It is at this stage that I would like to stress the significance of thinkers such as Ray Kurzweil with his ‘Law of Accelerating Returns’ and Aubrey de Gray – who both stress that man can and will live for far longer and that, indeed, there is no reason whatsoever why they cannot live forever.

Kurzweil: “I and many other scientists now believe that in around 20 years we will have the means to reprogramme our bodies’ stone-age software so we can halt, then reverse, ageing. Then nanotechnology will let us live forever…So we can look forward to a world where humans become cyborgs, with artificial limbs and organs” (The Sun, 2009.)

For Kurzweil this is a scientific inevitability – just as it is for him the fact that The Singularity will necessarily eventuate very soon via scientific development: the revelation in essence of the “Meaning of Life.’ Obviously, for him also, this is a very long way from the human-centred credos of Colin Wilson and his quoted experts such as Dr Darryl Reanney: “Time and self are outgrown husks which consciousness will one day discard” (Reanney, quoted in Wilson’s 2003 interview.) Ironically here, both Wilson and Kurzweil would – albeit from diametrically different tangents – support the notion of an impending singular explanation to ‘it all.’

What it all comes down to, for Ray Kurzweil however, is an initially purely physiological being, itself being augmented via a concatenation of technological bits and pieces so as to be able to continue ad infinitum and whereby consciousness would consist of perhaps not just brain cells, but a vast array of non-living implants so as to increase an individual life span to such a degree that there would be not only no ‘need’ for an afterlife, but that consciousness as Wilson et al sight it, has long since ceased to exist. As would what Colin Wilson equates to a transcendental ego-ed human – however god-like he envisages suchlike – per se. Indeed, even Wilson’s other quoted expert in the same source, Dr. Peter Fenwick with his belief that: “Mind may exist outside the brain and may be better understood as a field, rather than just the actions of neurons in the brain,” would seem to be abnegated by the potential scientific usurpation of Death. (Whither then, also, would be the transcendental ego-ed individual mind, one asks?)

For Aubrey de Grey (2005, online) also, longevity and ultimate eternal life are inevitabilities. His Engineered Negligible Senescence (SENS) project aims to overcome the seven causes of aging so that: “Basically we’ll have made the age related problems that we suffer from these days no longer an inevitable consequence of being alive…Once the technology is available, nearly everybody is going to want it…I think it’s reasonable to suppose that one could oscillate between being biologically 20 and biologically 25 indefinitely.” Like Kurzweil, de Grey sees considerable work on vaccines, drugs, gene therapy, stem cell therapy – and “much more high tech stuff” (ibid.) and even goes so far as to preach the ‘reversability’ of aging! His institute also runs the Methuselah Mouse prize for breakthroughs in extending the lifespans of mice and it is already worth over one million dollars – very similar here to Mark Zuckerburg et al’s Breakthrough Prize in Life Science, whereby awardees will have demonstrated evidence and the sequential steps to go about extending human life per se.

To me, Kurzweil and de Gray have confronted Death in the sense that they have argued for the abnegation of Death and are making determined efforts to bring this state about. This is a radically different negation or at least denial of the inevitable process of Death from that of the ‘they-self’ and also from the way in which Romantic idealists like Colin Wilson envisage Mankind somehow extending his or her consciousness both in life and in some potentially spectral afterlife – indeed they are insinuating the non-need for this to even need to happen in their basically socialist, non-elitist formulations of the inevitably available life-extension processes for everybody. Obviously, of course, both these factions in this tripartite equation as covered in this rather speculative article have come some considerable way from Heidegger and his belief that death is “not to be out-stripped” (ibid.) Quite the contrary.

The interesting aspect now is to explore briefly just how the Speculative Realists (the other faction) – who definitely share with them (de Gray, Kurzweil et al) the need for the superimposed status of ‘scientific rationalism’ and therefore the persuasive charter of the neurophysiologists – would segue into the notions and pragmatic explorations of de Gray and Kurzweil who are right out there, so to speak, in pushing science into the contemporary-beyond. To me, the two poles now split far apart: Brassier intends the: “trauma of scientific thought, the nihilism that inevitably goes with it, and the fact that this trauma indexes something unconditioned by human thought: something that has no interest in common with human survival or instrumentality” (Lindblom, ibid.) That given, science’s revelation of an ultimate universal meaninglessness does not also negate its ability to prolong life, human survival despite this: its mission is to introduce eternity on Earth. The overthrow of (Brassier’s) extinction is possible?

Then there is the quite odd Quentin Meillassoux: “Meillassoux believes that we can trace out the shape of the next event that will transcend humanity as we know it. Humanity’s great failing for Meillassoux is the cold, hard reality of death, which keeps human intellect from fulfilling its vocation to grasp the infinite. One might hope for something like the immortality of the soul in order to overcome this obstacle, but this would not fit the pattern that Meillassoux had established for the previous events. All of those transformative events rested on the foundation of the stage before it, while the immortality of the soul would simply leave embodied human existence (and hence the organic and material levels that provide its foundation) behind. The next stage of humanity must be material, must be organic and bodily — but it will be immortal. What’s more, this event will not apply solely to those who happen to be living when it happens. It must overcome the death of all human beings, allowing them to fulfill their vocation. Adam Kotsko (2012, online.) Meillassoux’s apocalyptic and radical vision would seem to be anticipating the plausible future arrival of some mega-human individual – God if you will – who will bring about eternity and a form of atonement even for the already departed. Echoes of Colin Wilson, actually!

The more practical response, methinks, would be to concur with Kurzweil et al and state that Death and extinction of Mankind – after all – may not be so damned inevitable, given the sheer alien non-humanity of its scope – and may be overcome. Lindblom (ibid.) yet again: “We might understand what he [Brassier] says, but then we still go shopping, talk about selves, emotions and so on.” Exactly – the ‘they-self’ continues to abjure such radically worrying visions of existence. I can only further emphasize from my own personal experience that when push comes to shove the desire to retain individual life overwhelms the drive to die, even in the face of a nihilistic universe: at death’s door, one finally wants to come back inside.

Now, with de Gray et al’s efforts my initial meta-question may well never need to be posed after all. Not only will we never die, we will also manifestly not be what we are now. There are – obviously – a wide raft of ethical and practical conundrums after this – to do with pragmatic realities as regards affordability and suitability of eternal candidature. More significantly, everything I have stressed here doesn’t die away: unless we overhaul to the silly ways we encourage death on this planet, we will continue to inhabit some death-denying ‘they world’ whereby we are gifted eternity or at the very least longevity beyond our ken, but stab ourselves in our own backs by our

Death lethargy. We all still need to be in awe of Death. It won’t ever actually depart.

All the more rationale to fight Death with every plausible weapon we have, eh.

Death is a very dull, dreary affair, and my advice to you is to have nothing whatsoever to do with it. W. Somerset Maugham

Personal Note:

Vaughan Rapatahana’s life has been a swill in death. Death had always been a shadow, losing parents and children far too early and unnecessarily. And he can certainly vouch that Albert Camus’ ‘solution’ didn’t work for him.

Now he wouldn’t wish Death on anyone, anywhere. Life is for seizing forever.