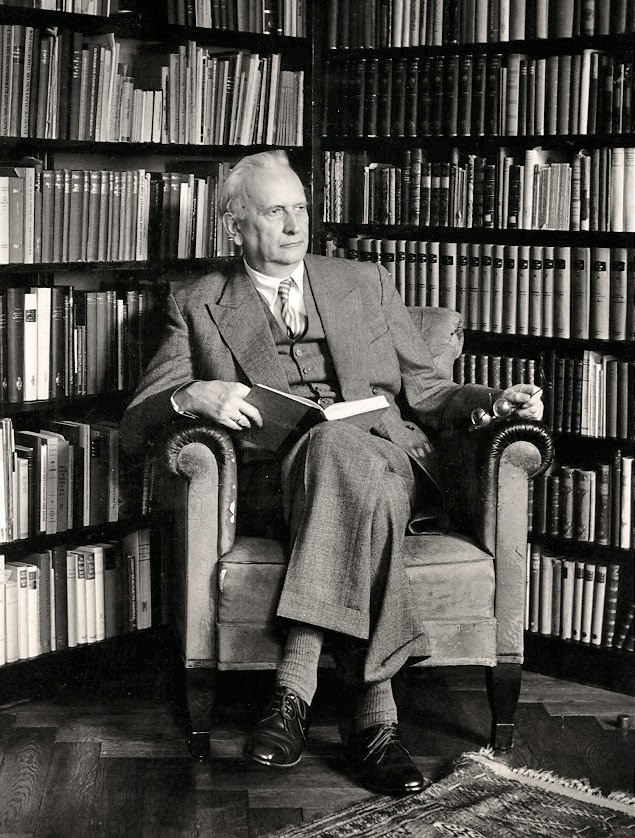

In the first volume of his Philosophy, an early (1932) work of the nascent Existentialist movement, Karl Jaspers argues “I do not become myself by smashing what is universal”. Weary of what he paradoxically describes as a “universal relativism” – the idea that anything and everything is valid from a viewpoint “which I can take, abandon and change” – he wryly explains that we can be at home in any standpoint “without standing for any”. The result of this ‘freedom’, he clarifies, is that we lose our genuine sense of self.

The novelist Robert Musil also noticed this rather self-indulgent psychological paradox around about this time when he described “the general obsession with turning every viewpoint into a standpoint and regarding every standpoint as a viewpoint”. Today this is known as ‘standpoint theory’. With roots in second-wave feminism, Foucault and Farnon, this ideology has stridently assured itself that it can realise full self-actualisation by smashing anything ‘universal’. It is therefore almost uncanny to read Musil’s novel The Man Without Qualities – from which the above quote is taken – and be told that “reason and progress in the Western world would be displaced by racial theories and street slogans”. With deadly accuracy, he described this “storm of aimless struggles” as merely “playacting”, a “splendid new gesture” or “vital pose” which “offers that moment of self-realisation”. Imagine, he writes, “what it is to have a heavy world weighing on tongues, hands and eyes […] and inside nothing but an unstable, shifting mist […] what a joy it must be whenever someone brings out a slogan in which one thinks one can recognise oneself”. Gurdjieff described this empty-headed banner waving as the “glamour of new slogans”. Like Musil and Jaspers, Gurdjieff was reacting to the chaos of a century ago. But again his words are are prescient. “There are periods in the life of humanity, which generally coincide with the beginning of the fall of cultures and civilisations, when the masses irretrievably lose their reason and begin to destroy everything that has been created by centuries and millenniums of culture”. These periods of “mass madness” he says, often coincide with “geological cataclysms, climatic changes, and similar phenomena of a planetary character”.

In A Criminal History of Mankind (1984) Colin Wilson defines relativism as the essence of the criminal mentality, presenting an abundance of ruined lives as examples. “You can’t say it’s wrong to kill. Only individual standards make it right or wrong” confided the murderer Melvin Rees. This, of course, is the logical conclusion of treating every viewpoint as a standpoint and vice-versa. But as Wilson observes, permitting free expression of such negative emotions is “the emotional counterpart of physical incontintence” with the result that the “inner being turns into a kind of swamp or sewage farm”. Aware of this baleful putrefaction of our objectivity, Jaspers describes it in a queasy but accurate phrase that sounds like a line from Arthur Machen’s The Novel of the White Powder – “the relativism that liquefies all things”.

Jaspers first came to attention in 1923 with his bulky tome General Psychopathology. Regarded as a significant landmark by Wilson in The New Existentialism (p. 108), it must be one of the first books to attempt to understand the criminal mind using the new techniques of phenomenology as developed by Jaspers’ contemporary Edmund Husserl circa 1900 (in Criminal History Wilson describes Husserl’s phenomenology as “the most important philosophical insight of the twentieth century”). Section V § 3 (b) of Jaspers book tantalisingly references studies on the “psychology of women poisoners” and “homesick girls who committed crimes”, and the first chapter, ‘Subjective Phenomena of Morbid Psychic Life (Phenomenology’)’ clearly shows the influence of the older thinker.

A 1955 Epilogue introduced the English translation of Jaspers’ three volume Philosophy. He recalls that the “philosophy I sought at universities in 1901 disappointed me” but “Husserl impressed me most, comparatively speaking, although his phenomenological method did not strike me as a philosophical procedure”. At first he took it – as Husserl himself originally did – as a name for descriptive psychology, and it is this ‘static’ phenomenology that Jaspers uses to power the argument of his Psychopathology. Jaspers also confided that when he met Husserl in 1913 “I told him I still failed to understand what phenomenology really was”. Characteristically, Husserl replied that understanding was a “difficult matter” but reminded Jaspers that he was already using the method perfectly anyway. “Just keep it up” was his sage advice. But looking back, Jaspers remembered that he had long rejected – in no uncertain terms – the later phenomenology that Husserl was developing when they met.

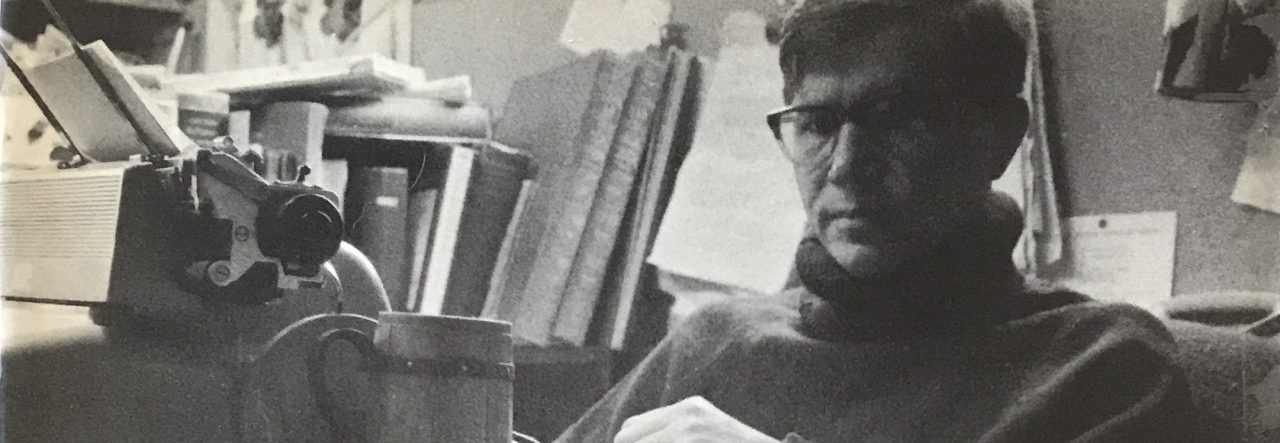

However, in The New Existentialism Wilson informs us that “Husserl’s aim is basically identical with that of Jaspers” in that he wants to create a flexible, lived philosophy. “Jaspers wants us to grasp knowledge as a living process, and the human relation to it as dynamic” (Wilson makes similar remarks about Sartre and Heidegger in his paper ‘The Mescalin Experience’, noting that due to its phenomenological roots, existential philosophy is active, ‘kinetic’, rather than static). One particular method that Jaspers had at his disposal to demonstrate this action was biography; simply describing the lives of philosophers illustrates an active philosophy beautifully (“Socrates’ father was a stonemason, his mother a midwife” begins the first chapter of the first volume of Jaspers’ breezily readable The Great Philosophers, 1957). Wilson used this method often, from The Outsider on – my personal favourite example from that book is of the young Nietzsche throwing himself into a corner of his sofa and devouring a second hand volume of Schopenhauer. Wilson acknowledged the debt to Jaspers many decades later. He comments that the point of the three volumes of Philosophy and the many volumes of The Great Philosophers is “to encourage the human mind to grasp its place in the great forward movement of the spirit”. Similarly Wilson’s The Outsider outlines the need for a lived philosophy in the fourth chapter.

Yet Wilson brands Jaspers “a failure” in The New Existentialism. In the sense that he meant it – of not really passing on vital results to philosophical successors, he is correct (Jaspers is little read today, even in philosophy departments). Then again, despite his obvious interest, Wilson describes the entire original ‘old’ (sic.) existential movement a failure a mere six pages later. But he insists that this is due to Jaspers, Heidegger, Sartre and Camus abandoning the important central insight of Husserl’s phenomenology which Wilson paraphrased as ‘perception is intentional’. Husserl’s advice to just keep up these disciplines even if Jaspers rejected them professionally was very honest and practical. Just keep it up could be a motto for Wilson’s own ‘new’ or ‘phenomenological existentialism’. “One of the reasons that the ‘old existentialism’ found itself immobilised was that it tried so hard to compromise with academic philosophy” observes Wilson, offering Jaspers as an example. Conversely Wilson’s The New Existentialism is written for “the ordinary intelligent reader”.

An important insight Wilson made in 1965 is that using the methods of the new existentialism – which are clearly described in the book of that title – involves the eventual recognition that that the truth is ‘within’ (subjective, as Kierkegaard observed) but it is not relative (Beyond The Outsider, p. 165). Heidegger defines the phenomenological method in Being and Time [§ 7] as one which does not subscribe to a single dogmatic standpoint. His teacher Husserl cheerfully waved away relativism in the introduction (Prolegomena) to the Logical Investigations, describing it as “a bare faced and (one might almost say) ‘cheeky’ scepticism” before patiently demolishing the arguments for relativism (‘psychologism’) piece by piece. “The essential core of this objection lies in the self-evident conflict between relativism and the inner evidence of immediately intuited existence” [Husserl, ibid. § 36]. In other words, relativism cannot accurately describe our inner states or existence, and taken further this relativistic attitude distorts everything. “The relativity of truth entails the relativity of cosmic existence” [ibid]. This attitude of universal relativism was espoused by Lovecraft in The Call of Cthulhu, with its famous opening line about the human mind being unable to correlate all its contents (a sentence which would have made Husserl grimace). In Order of Assassins (1972) Wilson postulated that had Lovecraft lived a little later, he could have included the ‘relativistic’ crimes of the serial killing age (“You can’t say it’s right or wrong to kill…”) in his panoply of unfolding horrors (“New York policemen are mobbed by hysterical Levantines” is one unintentionally funny line from the tale). Truth be told, Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos is a better illustration of “the relativism that liquefies all things” than anything by his master Machen.

Refuting this kind of shallow relativist view, explains Husserl, requires “the leverage of certain self-evident, universally valid convictions” [ibid. § 35]. From the start to the end of his career Wilson never gave up his conviction that we are living in the midst of an unseen perceptual revolution, holding a firm belief in an imminent evolutionary leap aided by intellectual investigations. This position, he admits in Beyond The Outsider (p. 181), is ‘strange and uncomfortable” unless our mental faculties are powerful – “the kind of power that can be given only by a deep conviction”. In previous religious ages these convictions were widely if naively held. Now the quest for the ‘transcendental ego’ gives us a conviction toward the possibility of ‘mystical’ experiences without ritual or yogic embellishments. Husserl referred to these layered powers as “hidden achievements” and our job – as phenomenologists – is to uncover and use them. Wilson sees the hidden achievements of this ego as evolutionary, a drive toward complexity.

The ‘transcendental” phenomenology that Jaspers rejected was detailed in Husserl’s Ideas, published the year they met. The second chapter of the third part is titled ‘Universal Structures of Pure Consciousness’ and begins by describing this ‘structure’ or “realm of transcendental consciousness” a primal region of absolute being in which relative mental states are merely dependant (and therefore not ‘universal’). As quoted in Herbert Spiegelberg’s The Phenomenological Movement (p. 160) and Wilson’s The New Existentialism (p. 62), Husserl later alluded to this mental space as the universalist domain of the transcendental ego and the ‘keepers of the key to the ultimate sources of being’ with reference to Goethe’s Faust. It sounds abstract and almost mystical – and let’s face it, exciting, which is perhaps the point – but Husserl is essentially describing a practicality, a ‘normal’ consciousness shorn of relativist prejudices – via his famous epoché – which leads to the mental state he describes as the ‘transcendental ego’. This is not a mystical ineffability but rather the beginning of clear philosophical thinking and it is analogous to Wilson’s observation that we recognise that the truth is within but is not relative. Husserl often reminded us that this phenomenological change starts with a change in attitude – Wilson’s ‘recognition’ (this word also forms an important insight at the very end of his 1997 book about the Sphinx).

Wilson’s slim 1980 monograph on the bicameral brain, Frankenstein’s Castle, describes this ‘switch’ from another angle. Referencing a theory of Howard Miller, an American doctor intrigued by hypnosis, Husserl’s transcendental ego is described by Wilson as a confused ‘normal’ ego. “This conclusion left me slightly stunned” he admits. “It was not quite what I had been expecting. We have become so conditioned to thinking of the ‘intellectual ego’ as a villain that I found my explanation disturbing. Surely, the correct answer should be: the transcendental ego – some ‘higher self’ that presides over consciousness?” This appeared to be Wilson’s position throughout the latter stages of his Outsider Cycle (1956 – ‘66), in books such as The Occult, 1971, and for quite a while after. Even so, in the sixth chapter of Beyond The Outsider – a fascinating book on ‘evolutionary intentionality’, a process tied in with Husserl’s concept of the transcendental ego – we read that uncovering this process merely involves bringing it to consciousness (“it had already taken place”). This phenomenological uncovering “is the act of going in search of the awareness long before it has reached the surface”. The literary example that Wilson gives is from Shaw’s Back to Methuselah; the maiden remarks to Strephon that “it is the realisation of it when it has actually happened” – ‘it’ being evolution, maturity. A theme that runs through Wilson’s work is that these happy discoveries appear to happen spontaneously without much control. Therefore Wilson thinks it is difficult to imagine exactly what type of creature ‘phenomenological man’ could be if he could completely uncover his intentional evolutionary structure and make these faculties a normal part of his consciousness (he later surmised that the results would likely be unpredictable but immense). The title of a later Wilson essay ‘Husserl and Evolution’ makes reference to this, as does his explanation that discovering Husserl’s “nonrelative philosophy” only made him aware of a process he had already been using. A recognition as much as a discovery.

Wilson describes Husserl’s phenomenology as an investigation into meaning. Therefore the starting point for this uncovering, explains Wilson, is a sense of meaninglessness, the classically existential type expressed in the opening sentence of his second autobiography Dreaming To Some Purpose. Jaspers notes in the third volume of Philosophy that the following states are contrary to meaning: “dissolution, death, lawlessness, crime, insanity, suicide, indifference, haphazardness” and last but not least, “absurdity”. All these dark themes are grappled with in Wilson’s writings and perhaps the key word here is ‘indifference’. Wilson’s notion of the ‘indifference threshold’ – our ‘normal’ state of consciousness where discomfort (or far worse) can stimulate us into happiness whereas comfort or even luxury bores us or makes us miserable – is vividly illustrated in his A Criminal History of Mankind. Like his book on the Sphinx, Criminal History has as its subtext the growing dominance of the careful but anxious left cerebral hemisphere over the ancient, pleasantly intuitive certainties of the right. This lopsided change was already observed in Beyond The Outsider with reference to Whitehead’s philosophy, but the paradox of the indifference threshold was best summed up in a line from Wilson’s book on the psychologist Maslow: that consciousness without crisis tends to become negative – a kind of psychic festering.

Jaspers argued that we know ourselves only in ‘boundary-situations’ – Foucault would later label these ‘limit-experiences’ – such as “death, suffering, guilt, the sudden violent accident” (The New Existentialism, p. 23; the concept is fully explored in the second volume of Jaspers’ Philosophy). But these – especially the last, haphazard example – surely are the same states, more or less, that he later regards as meaningless. Similarly both Heidegger and Gurdjieff thought that a grim realisation of impending death would ‘wake us up’ from our mechanised slumber – Dr. Johnson even had a cheerful quip about it – but Wilson sees this insight as poor phenomenology. Husserl wished to analyse mental states independent of the object or situation they were observing – technically, separating the noesis (perceptual acts) from the noema (content, or objects of intention). Wilson makes the interesting observation regarding this analysis by imagining what Husserl would have said about William Blake’s poetic philosophy in his 1965 essay ‘Phenomenology and Literature’, suggesting that we pursue the matter further by consulting the relevant texts. Apart from the fact that reading Blake makes one immediately aware what Wilson meant by the poet’s anticipation of phenomenology, Husserl thought [Ideas § 49] that the ideal phenomenological epoché would lead to nothing less than an “Annihilation of the World”, a psychic apocalypse which still leaves transcendental consciousness untouched. This is way beyond Foucault’s ‘limit-experiences’ but well within Blake’s imagination. A rare 1995 document containing marginalia from Wilson’s own copy of Introduction to The New Existentialism contains insights of a similar nature, questioning the ‘fake’ conscious mind and ruminating on the possibility that birth and death may be ‘intentional’ anyway (on the last page of his copy, Wilson had underlined his sentence “death may be a disguised form of suicide”). Further clues toward understanding this fascinating idea can be found in Wilson’s Afterlife and his biography of Rudolf Steiner, both from 1985.

Husserl’s thought experiment about the ‘annihilation of the world’ illustrates how far reality depends on perception. Accurate perception for Husserl, like Blake before him, depends on its intensity [see Logical Investigations, V § 19] or how accurately the perceptual arrow hits the object. When it does, it is “meant” [ibid. V § 21] and not partial or relative. Husserl goes on to say that this intwined ‘meant’ perception involving the act and content is correlative, a view which opposes Lovecraft’s bleak cosmic interpretation in the opening lines his Cthulhu story. Introducing his theory of ‘Faculty X’ (aka the ‘phenomenological faculty’) in The Occult Wilson remarks that we can only mean things when this Faculty is operative or as Husserl would say, we are in the phenomenological attitude. Wilson’s choice of Proust’s moment of insight in Swann’s Way as a perfect example of a faculty which reveals the reality of other times and places was insightful as Proust describes it wonderfully. It was “indisputable evidence [of] it’s reality […] in whose presence other states of consciousness melted and vanished”. It was, he recalls, a “neutral glow” – pure consciousness, identical to the universalist mental realm which Husserl delineated in Ideas.

Wilson informs us in The New Existentialism that the practical way toward this phenomenological universalism involves becoming constantly aware of the intentionality in all our conscious acts, hardly an impossible task. Here (p. 101) and in the previous ‘Outsider’ volume, Beyond The Outsider (p. 82) he insists that this can be done by anyone who goes to enough trouble. ‘Just keep it up’, as Husserl once said. Maslow explained that his patients had frequent ‘peak experiences’ the more they discussed them. Similarly Wilson noticed that “most people have insights to this effect [i.e. regarding ‘intentionality’] at least once a week”. We must, says Wilson, investigate these and give them philosophical weight (which of course, is exactly what he did). “One we see this clearly” he comments in The New Existentialism, “it becomes astonishing that anyone bothers to argue about it”. For anyone who can be bothered to take these disciplines seriously, that sentence is wryly amusing.

Wilson’s Order of Assassins ends with a thought about what happens when we are deprived of these larger meanings: we turn to sloganeering messiahs and führers and eventually turn bitter and violent. Against the rather helpless feeling that society has about such problems – and at the moment, it’s more of a rather drab, generalised sense of stasis or treading water – Wilson ended Criminal History by remarking that “all the major transformations in society have started with the few who know better”. And in the last paragraph of his Beyond The Occult he states that this will remain so until we stop merely marking time.

Works used:

Heidegger, Martin: Being and Time, Harper Collins, 1962

Husserl, Edmund: Ideas (book one) Marcus Nijhoff, 1983

Husserl, Edmund: Logical Investigations (2 volumes), RKP, 1970

Jaspers, Karl: General Psychopathology, Manchester University Press, 1972

Jaspers, Karl: The Great Philosophers, Harcourt, Brace and World Inc., 1962

Jaspers, Karl: Philosophy (3 volumes), University of Chicago Press, 1969-‘71

Lovecraft, H. P.: The Haunter of the Dark, Panther, 1970

Machen, Arthur: Tales of Horror and the Supernatural, Volume 2, Panther, 1975

Musil, Robert: The Man Without Qualities, (2 volumes) Picador, 1995

Ouspensky, P. D.: In Search of the Miraculous, RKP, 1950

Proust, Marcel: Swann’s Way, Vintage 1992

Spiegelberg, Herbert: The Phenomenological Movement: A Historical Introduction (2 volumes), Marcus Nijhoff, The Hague, 1976

Wilson, Colin: A Criminal History of Mankind, Mercury Books, 2005 (updated edition)

Wilson, Colin: Afterlife, Caxton, 2000 (updated edition)

Wilson, Colin: Author’s Emendations to Introduction to The New Existentialism, Maurice Bassett, 1995

Wilson, Colin: Beyond The Occult, Corgi, 1989

Wilson, Colin: Beyond The Outsider, Arthur Barker, 1965

Wilson, Colin: Existentially Speaking, Borgo Press, 1989

Wilson, Colin: From Atlantis to the Sphinx, Virgin, 1997

Wilson, Colin: New Pathways in Psychology, Gollancz, 1972

Wilson, Colin: Order of Assassins, Hart-Davis, 1972

Wilson, Colin: Rudolf Steiner: The Man and his Vision, Aquarian, 1985

Wilson, Colin: The New Existentialism, Wildwood House, 1980

Wilson, Colin: The Occult, Panther, 1978