NOTE: The Third Colin Wilson Conference will be happening this September (1st – 3rd) in Nottingham, UK. More details here.

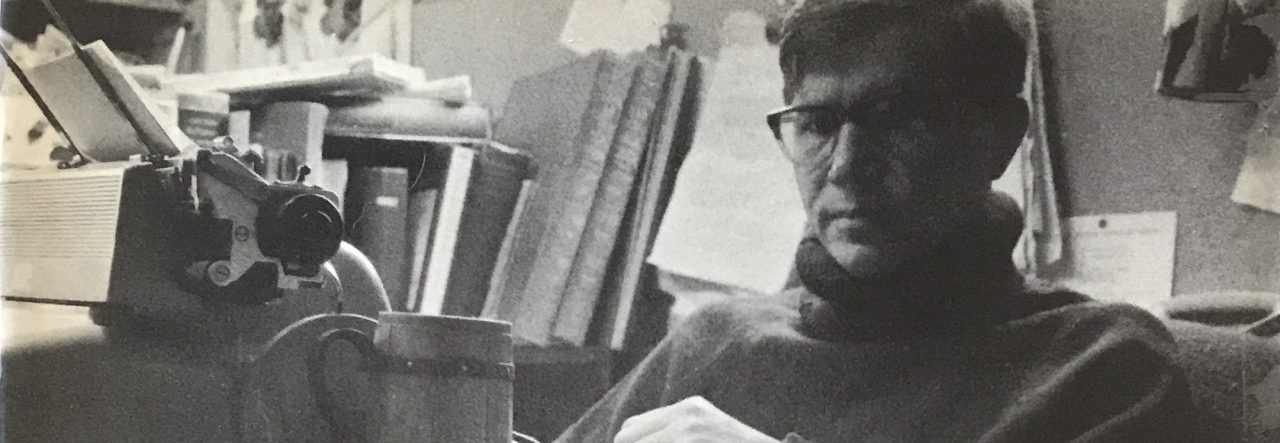

“It is the fallacy of all intellectuals to believe that the intellect can grasp life” wrote Colin Wilson in 1966. A century before, the young Nietzsche had realised that happiness and freedom lie beyond “the confusions of the intellect” when he took shelter in a shepherd’s hut. “The storm broke with a tremendous crash, discharging thunder and hail, and I had an indescribable feeling of well-being and zest”. Similarly, Proust’s epiphany in Swann’s Way happens on a dreary winters day. “The past” he broods as he comes indoors from the cold, is “beyond the reach of the intellect”. A few sips of warm tea and some morsels of cake later he recalls a childhood episode with piercing clarity; he has suddenly ceased to feel mediocre, accidental (“contingent” depending on the translation) or mortal. This feeling of “all-powerful joy”, he ruminates, brought with it “no logical proof, but the indisputable evidence, of it’s felicity, it’s reality”. Proust called these moments of well-being moments bienheureux – “quite simply, a surge of strength and power” comments Wilson. He goes on to say that Proust would have demurred at this interpretation as he thought of himself as an invalid and hypochondriac. Conversely, Nietzsche sought this powerful feeling despite his own worse ill-health (Wilson’s 1972 essay Dual Value Response examines the latter dichotomy in some detail). In 1986 Wilson defined existentialism – as it is commonly understood – as “the notion that reality extends beyond our power to grasp it”. Against this he offered a ‘new’ existentialism, based on the phenomenological methods of the philosopher Husserl. The key text, Introduction to The New Existentialism (1966) explains how Husserl’s ideas deny the contingency that existentialism stressed, despite predating and influencing that philosophical school. Both Heidegger and Sartre began as keen ‘phenomenologists’, the former studying it first hand from Husserl. Wilson correctly points out that both soon moved away from Husserl’s most practical insight, that of intentionality, or the study of active perception, in order to compromise with professional philosophy (and with dogmatic political ideology, Heidegger veering far right and Sartre far left).

The intellect finds it hard to grasp the moments which Nietzsche and Proust experienced as it relies on the shorthand of symbols and language, puzzles which Wilson examines in the last few volumes of the Outsider series. But these – indeed, most of his books – also analyse a much more serious and immediate problem: the seemingly random fluctuations of consciousness. “If the flame of consciousness is low” he writes in The New Existentialism, “a symbol has no power to evoke reality, and intellect is helpless”. That the intellect is a “false guide” is no cause for pessimism, he comments, as pessimism itself arises from from the delusions of passive, limited consciousness. “Human beings need a centre of security from which to make forays into the outer-chaos”, he continues. But these protective walls can quickly feel like a padded cell or prison; too much security becomes boredom which leads to a loss of vitality, a feeling of being trapped in the present. This atmosphere is described in the first part of Goethe’s Faust, in Goncharov’s Oblomov and in Sartre’s fiction. “Man uses his intellect to prevent his experience from escaping him” comments Wilson. “But the essence of the experience escapes, all the same”. Existence philosophy (‘old’ existentialism, as Wilson labels it) failed because it stuck to examining everything through this narrow lens of limited consciousness. Adding insult to injury, it declaimed these limitations in the formal jargon of the academy (“the difficulties encountered in a text by Jaspers, Heidegger or Sartre are the difficulties that the author feels to be necessary to an academically respectable philosophy”). But the point of Existenzphilosophie was that it dealt with direct living problems over generalised abstractions, a realistic attitude which Wilson attempted to revive with his vigorous ‘new’ or phenomenological existentialism, aimed at the general rather than specialist reader. “It deals with the most immediate problem we can experience, with our actual living response to everyday existence”. It could be argued that Wilson’s background as a self-taught working man gives his writings a directness and liveliness which is generally missing in the theorists he is examining. It also offers accessibility to a non-academic audience, a point he addresses early in his book. I can vouch for that, as The New Existentialism is the most useful text I’ve read for dealing with the seemingly random fluctuations of meaning which come and go on a daily basis. Simply put, the phenomenological idea of intentionality suggests that we subliminally select our meanings according to our temperament. Nietzsche intuitively grasped this process when he said that there are no facts, only interpretations, but Husserl went further, demonstrating that our interpretations cloud these ‘facts’ or truths. Understand these distortions and we will begin to think with more clarity.

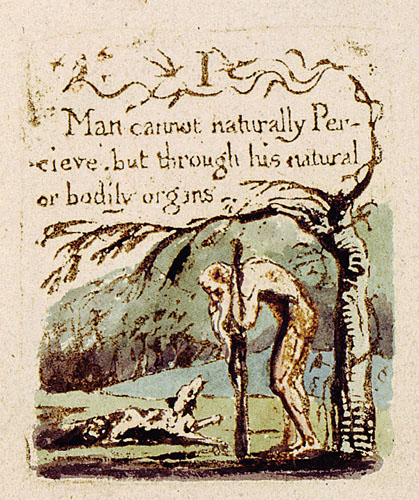

If this principle of intentionality is understood, life gradually becomes subtly different. “Once we see this clearly, it becomes astonishing that anybody bothers to argue about it” reads one of the most penetrating lines in Wilson’s book. About what? About the observable principle that intentionally limited consciousness – what we glibly call ‘ordinary consciousness’ – is a scaled down version of the real thing, a truncated view of life. This is not wooly mysticism – Wilson had already offloaded mystical literature to the status of a “primitive phenomenology” in the previous Outsider volume. As he says, it has more to do with our direct response to everyday existence. If consciousness selects it’s facts and objects of perception, why would anyone choose a selection which ‘proves’ that they are merely at the mercy of outward things, without any inner freedom? The obvious answer is: laziness. But as Husserl stated in 1900, an energetic perception grasps more ‘reality’ than a merely token recognition, an observation previously made by the poet Blake with his devilish aphorism ‘energy is eternal delight’. This optimistic sense of lived possibility runs through all Wilson’s writing. “Can one live a philosophy without negating either the life or the philosophy?” he asked in the opening pages of The Outsider. Yes: as he later explained in Beyond the Outsider, the workings of intentionality “can be observed by anyone who goes to enough trouble”. Effort is the starting point; this could merely be the effort to understand what Husserl meant. The New Existentialism even has a section of practical disciplines. “The first practical disciple for the existential philosopher is to learn to become constantly aware of the intentionality of all his conscious acts”. Recognition is another key factor.

Husserl himself insisted that phenomenology is not merely “vocational” or academic but involves creating a new attitude [Einstellung] towards lived experience. Wilson put it succinctly in a later essay on his ‘new’ existentialism in 1986: “Husserl’s recognition of the intentionality of consciousness is a recognition that our attitudes govern our perceptions”. Wilson’s writings are packed with illustrations of this in action. Examples are drawn from from literature or philosophy – Proust and Nietzsche, above – or from religion and mysticism, psychology, personal anecdote, even criminal cases. He would often quote the philosopher Whitehead, who had insisted we examine ‘experience drunk and experience sober’ – Wilson wrote a book on alcohol – ‘experience normal and experience abnormal’ and so on. This is the existentialist position (Wilson also wrote an essay about Whitehead as an existentialist). It is what Husserl meant when he said that the study of intentionality is not vocational but is completely involved in life as a whole. “We can even go on calmly speaking in the way we must as natural human beings” writes Husserl in the sixty-fourth section of Ideas, “for as phenomenologists we are not supposed to stop being natural human beings”.

Wilson thought Husserl’s method “brilliant and original” but felt that he never really got beyond it (“he spent his life on the threshold of philosophy, laying the ‘foundations’”). What was required of his own use of this method was to align it with the everyday experience of the average reader, and to tackle the serious problem of fluctuating meaning. Wilson was adamant that intentionality was much more exciting and dynamic than ‘reference to an object’ or an ‘intelligent effort of interpretation’ as phenomenologists soberly put it.

Husserl speaks of intention as a “ray” or “grip” while pondering how to regenerate the confusions of “intellectual content” into something distinctive and understandable [Ideas § 123]. Wilson points out in Dual Value Response that if Nietzsche had lived to his sixty-eighth year and read Husserl’s text he would have found a direct method for grasping his pure experience, without intellectual confusions. Not only that, says Wilson; had Nietzsche known about separating his intention from the object – which Husserl explains in great detail between sections 87 and 127 of Ideas – we would have been spared his unnecessary obsessions with the likes of “that egotistic roughneck” Cesare Borgia. With this concept in mind Wilson spoke of a faculty which can firmly hold a “grip on reality” in The Strength to Dream and of intentionality as an “inner meaning” or “grip on life” in Origins of the Sexual Impulse. “Husserl’s phenomenology, then, is an investigation into meaning” he says in Beyond the Outsider. These last few volumes of the Outsider series are where Wilson delves deepest into phenomenology, all of it summarised in the 181 pages of The New Existentialism. Here, the ideas of the Outsider series are presented in “a simple and non-technical language for the ordinary intelligent reader” and Wilson presupposes no previous knowledge of the series, nor the existentialism or phenomenology it deals with. One delightful aspect of the book is it’s tone: it manages to explain ‘continental’ philosophy with the breeziness of an Anglo empiricist. “A phenomenologist might be an existentialist or a logical positivist or a neo-Hegelian” he writes, ending the first part of the book (“little more than a clearing of the ground”). But it is already much more than that. The first part remains one of the most cogent explanations of the phenomenological method ever written, and one of the main reasons for such dynamic clarity is that Wilson was a self-motivated thinker, a product of factory floors and belching chimneys rather than dreaming spires and ivory towers. Nietzsche himself said that good writers attempt to make their ideas clearly understood rather than cypher them to “knowing and over-acute readers” of the over analytical, dryly intellectual kind. “The legitimate is simple, as all greatness is simple, open to anyone’s understanding” wrote the novelist Robert Musil in his masterpiece, The Man Without Qualities. “Homer was simple, Christ was simple. The truly great minds always come down to simple basics”. If Nietzsche had written a novel, it would doubtless read like Musil’s (despite one character describing him as a “mental case”!)

The intellect can only take us so far in these matters as it is still only a part of lived experience, entwined with our values and our response to life. The phenomenological methods on which the new existentialism is based do not promise instantaneous results or a quick fix solution. “You can’t become a new human being overnight” as Musil observed. Rather, it is closer to the religious idea that a) what we observe is not the totality of reality and b) more subtle aspects of this reality can be slowly comprehended over the span of adult life via careful observation. However, the method is free of the kind of sectarian prejudices (“the weaknesses of every individual” as Blake had it in All Religions Are One) that inevitably sink religions and their cultish offshoots.

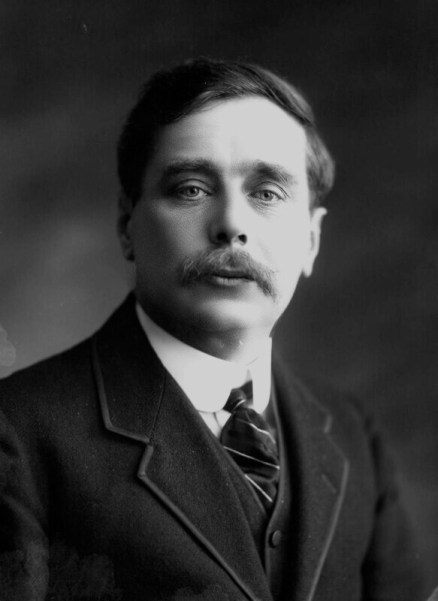

In a social sense it is important to remember that Wilson equates early lack of struggle with the attitudes toward meaning that Husserl describes. For instance, Sartre and Beckett were brought up comfortably middle class whereas Shaw and Wells – and Wilson himself – were working class. The tone or atmosphere of the new existentialism is therefore closer to the latter writers than the former, based as it is on the ordinary lived experience of difficulty, the hard won knowledge that effort brings reward.

But perhaps the reason I personally find Wilson to be a trustworthy guide in many intellectual matters is due to a shared attitude – what the psychologist Maslow called ‘the need to know’, the opposite of intellectual timidity or logical dogmatism – rather than the specific fact that we both emerged from the same rung of society (correctly, Wilson never liked being bricked in as just a ‘working class writer’ with his fellow Angry Young Men). Most likely, it was this open attitude rather the bare facts of Wilson’s background which created his uneasy relationship with the intelligentsia of the time.

Maslow remarks that “examination of psychologically healthy people shows pretty clearly that they are positively attracted to the mysterious, the unknown, to the puzzling and the unexplained”, the kind of amusing or disturbing oddities collected by Madame Blavatsky or Charles Fort or indeed in Wilson’s own, rather more literate and philosophical occult studies. Maslow observed that psychologically unhealthy subjects tend to feel threatened by the ambiguous and unfamiliar, preferring the “unenriched familiarity” of normal or naive perception as Husserl described it (Wilson had it as “forced familiarity” in his Wilhelm Reich biography). Sartre’s writings contain many examples of this easily upset perception, notably the descriptions in Nausea of trees which frightened him and lamp-posts which embarrass him (“I would have liked them to exist less strongly, in a drier, more abstract way”). As Nietzsche said, we begin to distrust clever people when they embarrass too easily. Sartre’s request is admirably ‘phenomenological’, but one which misunderstands Husserl’s assertion of an active perception. True to form, he felt more comfortable with dialectical materialism.

One of the practical phenomenological disciples given in The New Existentialism involves patiently listening to political opinion from the party you vote against without reacting – a challenge indeed to the hardened dogmatists of both left and right today. Wilson’s A Criminal History of Mankind (1985) overflows with illustrations of this “spiritual arthritis” at work in societies and individuals throughout history. Such rigid dogma can easily become a catastrophic, anti-creative force, reactive rather than intentional. Wilson’s favourite mystic Gurdjieff was obsessed with overcoming this ‘mechanical’ fault, stressing that genuine knowledge is only allotted to those who actively seek it via struggle or effort. This information, he says, can be best collected during the fall of cultures, “when the masses lose their reason and begin to destroy everything” – periods of philistinism often accompanied by “geological cataclysms, climatic changes”. An enormous surplus of this ‘knowledge’ lies unclaimed as the majority never even collect their rationed share (Gurdjieff insisted that knowledge was ‘material’, like food). It’s certainly a good parable for Wilson’s analysis of meaning, which can be grabbed or grasped in larger quantities by those who have attempted to develop their ‘organ’ of intentionality (“a kind of hand” as Wilson describes it). This can only be done on an individual level; no one else can do it for you. Gurdjieff also insisted that the only possible mystical initiation is self-initiation. As Wilson suggested, the mystical doctrines of ancient sects are but a precursor to Husserl’s revolution in thought.

Wilson sometimes said that this question of intentionality was a matter of life and death, a seemingly large and dramatic claim for an abstract philosophy born of logic (Husserl began as a mathematician). But in a certain sense it is true: those capable of developing a hold or grip on reality will be far less susceptible to debilitating conditions such as depression. Drawn from a passage near the end of The New Existentialism, the plot of Wilson’s 1967 satire The Mind Parasites outlines a global plague of anhedonia circa – ahem – now. The narrator describes the book (essentially an assemblage of fictional documents) as “a work of history, not of philosophy” but is still of the opinion that the word phenomenology is “perhaps the most important single word in the vocabulary of the human race”. Satire or no, it is likely that Wilson wrote that line with his tongue only partly in his cheek.

In the long run Wilson’s one man war against life-failure and the ‘age of defeat’ will become more and more relevant to hardened individualists bored by living in a rather suffocating world modeled on he philosophical fallacies of behaviourism, a system which maintains the lifeless state of the “man-machine” that Gurdjieff regarded with horror. “Husserl suggested” writes Wilson in The New Existentialism “that as man loses all the false ideas about himself and the world through scientific [i.e. phenomenological] analysis, and as he comes to recognise that he himself is responsible for so much that he assumed to be ‘objective’, he will come to recognise his true self, presiding over perception and all other acts of living. This idea seems common-sensible enough, and our intuitions about ourselves seem to support it”. A few examples of this shift happening are given later in the book via the experiences of William James, Arthur Koestler and René Daumal. “The ‘self’ that has been experiencing various fears and humiliations has been evoked by a narrow range of experience”, but the self that has overcome this “is contemptuous of this triviality”. This the change of attitude (suspension of prejudices) which Husserl stressed. By true self or ‘transcendental ego’ he meant a state shorn of fallacies from which genuine thought could begin. But Sartre, and later Derrida (“Sartre redivivus” – Wilson) misunderstood it as a survival of religious idealism, thanks to too much dogmatic intellectualism and not enough common-sense intuition.

The key, as Husserl said, is to become aware of the workings of intentionality as a living method, rather than just another theory in the annals of philosophical history. “In recent times the longing for a fully alive philosophy has led to many a renaissance” he states in the lecture Cartesian Meditations [§ 2]. This living philosophy is based on the “radicalness of self-responsibility”, and on a necessity to “make that radicalness true for the first time by enhancing it to the last degree”. This “new beginning”, he says, is “each for himself and in himself” [§ 3]. In Beyond The Outsider Wilson remarks that Kierkegaard’s ‘truth is subjectivity’ can really only be illuminated by Husserl’s method. Rather than interpret this as ‘beauty being in the eye of the beholder’ it should be understood as a paradoxical instruction meaning that truth is within (“in himself”) but is not relative. Wilson later comments that Kierkegaard’s statement “seems to justify the view that there are as many ‘truths’ as there are individuals, and all are equally valid”, which is the default position of the present era. [1] Musil sardonically wrote of “the general obsession with turning every viewpoint into a standpoint and regarding every standpoint as a viewpoint”, a barb as relevant as it was a century ago. Wilson goes on to say that it would be more accurate to say that ‘truth is evolutionary intentionality’ (a concept explained at length in Beyond The Outsider). In effect this means that the further we move away from local or subjective prejudices – Blake’s ‘weaknesses’ – the closer we get to a truly unique individuality (the transcendental ego, a self shorn of such relativist baggage). As previously noted, our deeper intuitions about ourselves certainly support this view.

The evolutionary paradox which Wilson analyses in titles such as Beyond The Outsider, The Occult and A Criminal History is of a lopsided human creature dominant in intellect and it’s ever refined details but surprisingly weak in grasping larger, overall meanings. As his philosophy aimed to correct this disability, it is unsurprising that he came into conflict with professional intellectuals as much as he was welcomed by ordinary readers. After all, as The New Existentialism explains, that was his intention all along.

[1] “If we instinctively acknowledge human greatness as a value – that is, if we agree that Jesus is in some way preferable to Judas Iscariot, that Beethoven is a more valuable human being than Al Capone – then we are subscribing to he basic human vision of freedom”. Wilson, Colin, Introduction to The New Existentialism, Hutchinson, 1966, pp. 162/3. This is analogous to Wilson’s comment on Nietzsche’s unnecessary celebration of the Borgias (“a great deal of misleading stuff”). Wilson, Colin, ‘Dual Value Response’, 1972. Collected in The Bicameral Critic, Salem House, 1985, p. 108.

Wilson has dealt with the historical schisms of the original phenomenological movement in some of his writings but what really concerned him was making his readers understand and practice the discipline of becoming aware of and controlling our selective acts in perception, to grasp our freedom to choose whichever angle we see the world from. Nietzsche called this choice of viewing angles ‘perspectivism’ but was unaware of the beginnings of what one historian has called the “phenomenological current” which started with Franz Brentano. [2] Nietzsche’s swooping “guerrilla raids” on presuppositions (our ‘colouring’ attitudes) make enthralling and inspiring reading, but he lacked Husserl’s basic technique to truly explode them. A guerrilla, Wilson commented, “is at a psychological disadvantage, being a man without with a home, without an established position”.

Wilson has dealt with the historical schisms of the original phenomenological movement in some of his writings but what really concerned him was making his readers understand and practice the discipline of becoming aware of and controlling our selective acts in perception, to grasp our freedom to choose whichever angle we see the world from. Nietzsche called this choice of viewing angles ‘perspectivism’ but was unaware of the beginnings of what one historian has called the “phenomenological current” which started with Franz Brentano. [2] Nietzsche’s swooping “guerrilla raids” on presuppositions (our ‘colouring’ attitudes) make enthralling and inspiring reading, but he lacked Husserl’s basic technique to truly explode them. A guerrilla, Wilson commented, “is at a psychological disadvantage, being a man without with a home, without an established position”. We have forgotten that most of our mechanical actions were originally intentional and live robotically as a consequence – what Husserl called our “well known forgetfulness”, a concept later appropriated by his pupil Heidegger. Husserl’s phenomenology has much in common with the anti-robotism of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky who also concerned themselves with remembering the self via constant and vigilant meditation on the mechanicalness (sic.) of the body, it’s actions, the emotions and perception. To get around this mechanical illusion we must not forget that our intentions are willed. For Husserl, the body is an “organ of the will”, what Nietzsche meant by the will to power and Blake saw as a dynamic extension of the Poetic Genius. This keen awareness that our ‘mechanicalness’ is layer upon layer of willed intentions is the choice between the naive and phenomenological attitudes or worlds. [6] It is the choice between ‘meaninglessness’ and meaning – the former can appear valid in the naively nihilistic attitude but like ‘mechanicalness’ it is merely the product of a narrow, partial perception, a “feeling isolated in a world of objects” as Wilson puts it. In the early pages of Nausea Sartre accurately describes this state when observing a cafe proprietor – “when his establishment empties, his head empties too […] the waiters turn out the lights, and he slips into unconsciousness: when this man is alone, he falls asleep” – a statement that Gurdjieff would have perhaps appreciated (Wilson noted in his debut that ‘Outsiders’ have no problem being alone). Our consciousness is selective but as Wilson points out an “enormous area of [our] own being is inaccessible to the beam of consciousness” (the ‘beam’ is intentionality or selectivity; Husserl used the term ‘ray’).

We have forgotten that most of our mechanical actions were originally intentional and live robotically as a consequence – what Husserl called our “well known forgetfulness”, a concept later appropriated by his pupil Heidegger. Husserl’s phenomenology has much in common with the anti-robotism of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky who also concerned themselves with remembering the self via constant and vigilant meditation on the mechanicalness (sic.) of the body, it’s actions, the emotions and perception. To get around this mechanical illusion we must not forget that our intentions are willed. For Husserl, the body is an “organ of the will”, what Nietzsche meant by the will to power and Blake saw as a dynamic extension of the Poetic Genius. This keen awareness that our ‘mechanicalness’ is layer upon layer of willed intentions is the choice between the naive and phenomenological attitudes or worlds. [6] It is the choice between ‘meaninglessness’ and meaning – the former can appear valid in the naively nihilistic attitude but like ‘mechanicalness’ it is merely the product of a narrow, partial perception, a “feeling isolated in a world of objects” as Wilson puts it. In the early pages of Nausea Sartre accurately describes this state when observing a cafe proprietor – “when his establishment empties, his head empties too […] the waiters turn out the lights, and he slips into unconsciousness: when this man is alone, he falls asleep” – a statement that Gurdjieff would have perhaps appreciated (Wilson noted in his debut that ‘Outsiders’ have no problem being alone). Our consciousness is selective but as Wilson points out an “enormous area of [our] own being is inaccessible to the beam of consciousness” (the ‘beam’ is intentionality or selectivity; Husserl used the term ‘ray’).  As Wilson has noted, consciousness without crisis tends to become negative. We appear to be mostly unable to appreciate things until they’re threatened or have disappeared completely. When they’re in front of us we regard them with indifference, boredom or they’re simply not noticed at all. His concept of the threshold illustrates the “curious inadequacy of human consciousness”, our very limited capacity for freedom – Nietzsche understood it as freedom ‘from’ (passive) rather than freedom

As Wilson has noted, consciousness without crisis tends to become negative. We appear to be mostly unable to appreciate things until they’re threatened or have disappeared completely. When they’re in front of us we regard them with indifference, boredom or they’re simply not noticed at all. His concept of the threshold illustrates the “curious inadequacy of human consciousness”, our very limited capacity for freedom – Nietzsche understood it as freedom ‘from’ (passive) rather than freedom

The Second International Colin Wilson Conference; University of Nottingham, Kings Meadow Campus, Lenton Lane, Nottingham, NG7 2NR. To be held on Friday the 6th of July, between 9:30 – 17:10. Eight speakers will present papers, there will be discussion, refreshments, and a tour of the huge Colin Wilson archive housed in the University. There are only 55 places in total and tickets for Friday are £36.50 – email Colin Stanley at stan2727uk@aol.com or call/fax 0115-9863334. Please be aware that tickets will sell fast. There will also be a rare chance to see an operetta co-authored by Colin Wilson on Saturday – for those who wish to attend both this and the conference the ticket price is £42.

The Second International Colin Wilson Conference; University of Nottingham, Kings Meadow Campus, Lenton Lane, Nottingham, NG7 2NR. To be held on Friday the 6th of July, between 9:30 – 17:10. Eight speakers will present papers, there will be discussion, refreshments, and a tour of the huge Colin Wilson archive housed in the University. There are only 55 places in total and tickets for Friday are £36.50 – email Colin Stanley at stan2727uk@aol.com or call/fax 0115-9863334. Please be aware that tickets will sell fast. There will also be a rare chance to see an operetta co-authored by Colin Wilson on Saturday – for those who wish to attend both this and the conference the ticket price is £42.